In America, the events of the early part of the twentieth century created what could be considered a perfect storm for social change, and that led to one of the most controversial and widely misunderstood legacies of our 32nd President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His New Deal for America was a series of domestic programs enacted between 1933 and 1936 (and a few which came later), designed to transform America’s economy after the stock crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression.

In America, the events of the early part of the twentieth century created what could be considered a perfect storm for social change, and that led to one of the most controversial and widely misunderstood legacies of our 32nd President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His New Deal for America was a series of domestic programs enacted between 1933 and 1936 (and a few which came later), designed to transform America’s economy after the stock crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression.

Taking office on March 4, 1933, the jovial, optimistic, and confident Roosevelt assumed the presidency during a time of great crisis for the nation, with millions of people underemployed or unemployed. The country’s industrial production had fallen dramatically, the agricultural economy was in chaos, and the banking system had become paralyzed as a widening panic drained banks of their deposits. Michigan’s governor had closed all the banks in his state, and almost every state in the nation had placed some restrictions on banking activity.

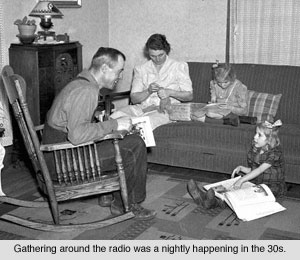

On Sunday, May 7, 1933, families all across America tuned in their radios and listened as the National Broadcasting Company and the Columbia Broadcasting System aired one of President Roosevelt’s avuncular Fireside Chats, titled Outlining the New Deal Program. In the middle of his speech he described the paradox which necessitated taking unprecedented steps to bring about lasting change:

On Sunday, May 7, 1933, families all across America tuned in their radios and listened as the National Broadcasting Company and the Columbia Broadcasting System aired one of President Roosevelt’s avuncular Fireside Chats, titled Outlining the New Deal Program. In the middle of his speech he described the paradox which necessitated taking unprecedented steps to bring about lasting change:

“I feel very certain that the people of this country understand and approve the broad purposes behind these new governmental policies relating to agriculture and industry and transportation. We found ourselves faced with more agricultural products than we could possibly consume ourselves and surpluses which other nations did not have the cash to buy from us except at prices ruinously low. We found our factories able to turn out more goods than we could possibly consume, and at the same time we have been faced with a falling export demand. We have found ourselves with more facilities to transport goods and crops than there were goods and crops to be transported. All of this has been caused in large part by a complete failure to understand the danger signals that have been flying ever since the close of the World War. The people of this country have been erroneously encouraged to believe that they could keep on increasing the output of farm and factory indefinitely and that some magician would find ways and means for that increased output to be consumed with reasonable profit to the producer.

“But today we have reason to believe that things are a little better than they were two months ago. Industry has picked up, railroads are carrying more freight, farm prices are better, but I am not going to indulge in issuing proclamations of over-enthusiastic assurance. We cannot ballyhoo ourselves back to prosperity. I am going to be honest at all times with the people of the country. I do not want the people of this country to take the foolish course of letting this improvement come back on another speculative wave. I do not want the people to believe that because of unjustified optimism we can resume the ruinous practice of increasing our crop output and our factory output in the hope that a kind providence will find buyers at high prices. Such a course may bring us immediate and false prosperity but it will be the kind of prosperity that will lead us into another tailspin.”

“But today we have reason to believe that things are a little better than they were two months ago. Industry has picked up, railroads are carrying more freight, farm prices are better, but I am not going to indulge in issuing proclamations of over-enthusiastic assurance. We cannot ballyhoo ourselves back to prosperity. I am going to be honest at all times with the people of the country. I do not want the people of this country to take the foolish course of letting this improvement come back on another speculative wave. I do not want the people to believe that because of unjustified optimism we can resume the ruinous practice of increasing our crop output and our factory output in the hope that a kind providence will find buyers at high prices. Such a course may bring us immediate and false prosperity but it will be the kind of prosperity that will lead us into another tailspin.”

During Roosevelt’s first Hundred Days many acts were introduced which were to form the basis of the New Deal and cover issues of social, economic, and financial concern. By forging a coalition which included banking and oil industries, state party organizations, labor unions, farmers, blue collar workers, minorities (racial, ethnic and religious), and others, Franklin D. Roosevelt created support for his New Deal plan.

During Roosevelt’s first Hundred Days many acts were introduced which were to form the basis of the New Deal and cover issues of social, economic, and financial concern. By forging a coalition which included banking and oil industries, state party organizations, labor unions, farmers, blue collar workers, minorities (racial, ethnic and religious), and others, Franklin D. Roosevelt created support for his New Deal plan.

An enthusiastic, genial, but dominant leader who was swept into the Presidency in an unprecedented wave of popularity, and with the bouncy popular song “Happy Days Are Here Again” as his campaign theme, many of Roosevelt’s acts were passed without too much scrutiny. In later years the Supreme Court declared some acts in the New Deal were unconstitutional, including the National Industrial Recovery Act, and the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act. But others became part of the fabric of our government, such as the Emergency Banking Act/Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Securities Act of May 1933/ Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act), the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, and the Social Security Act, which established a system that provided old-age pensions for workers, survivors benefits for victims of industrial accidents, unemployment insurance, and aid for dependent mothers and children, the blind and physically disabled.

An enthusiastic, genial, but dominant leader who was swept into the Presidency in an unprecedented wave of popularity, and with the bouncy popular song “Happy Days Are Here Again” as his campaign theme, many of Roosevelt’s acts were passed without too much scrutiny. In later years the Supreme Court declared some acts in the New Deal were unconstitutional, including the National Industrial Recovery Act, and the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act. But others became part of the fabric of our government, such as the Emergency Banking Act/Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Securities Act of May 1933/ Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act), the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, and the Social Security Act, which established a system that provided old-age pensions for workers, survivors benefits for victims of industrial accidents, unemployment insurance, and aid for dependent mothers and children, the blind and physically disabled.

The New Deal also introduced numerous new agencies which worked with the Federal government, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the Farm Credit Administration, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). It was this last agency which established the Matanuska Colony.

The New Deal also introduced numerous new agencies which worked with the Federal government, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the Farm Credit Administration, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). It was this last agency which established the Matanuska Colony.

~ ~ ~

On June 25, 1934, Time magazine featured the charismatic but controversial agricultural economist Rexford G. Tugwell on its cover. Tugwell was one of the core of Columbia University professors who formed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s infamous “Brain Trust,” the academics who helped develop policy recommendations leading to Roosevelt’s 1932 election as President. Tugwell subsequently served in FDR’s administration, and he became the primary architect of the New Deal.

Formed under the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the Resettlement Administration (RA) was the urbane, intellectual Rexford Tugwell’s brainchild, formed to relocate struggling urban and rural families to communities planned by the federal government.

In her landmark book, We Shall Be Remembered (Metropolitan Press of Portland, Oregon, 1966), Evangeline Atwood, who arrived in Anchorage with her husband, Bob Atwood, publisher of the Anchorage Times, only a month after the Colonists arrived in Palmer, wrote about Rexford Tugwell and the Resettlement Administration:

In her landmark book, We Shall Be Remembered (Metropolitan Press of Portland, Oregon, 1966), Evangeline Atwood, who arrived in Anchorage with her husband, Bob Atwood, publisher of the Anchorage Times, only a month after the Colonists arrived in Palmer, wrote about Rexford Tugwell and the Resettlement Administration:

“With nearly one hundred rural communities in the mill, Tugwell decided that the only way to keep them from decaying into rural slums would be to develop commercial agricultural units. Only through collective operation of the land could this be possible, so he decided that all farming projects should be cooperative. The RA would bring in a project manager, a farm manager, and a home supervisor who would help the settlement form consumers’ cooperatives. The agency would also purchase heavy farm machinery for the community and make individual loans for operating stock.”

The Matanuska Colony, Fifty Years 1935-1985 (Matanuska Impressions Printing, Palmer, Alaska 1985), by Brigitte Lively, notes that the Matanuska Colony Project was the only colony ever established in the United States. Lively also points out “…the project and the project people were celebrated and at the same time overwhelmingly criticized and condemned to failure.”

The Matanuska Colony, Fifty Years 1935-1985 (Matanuska Impressions Printing, Palmer, Alaska 1985), by Brigitte Lively, notes that the Matanuska Colony Project was the only colony ever established in the United States. Lively also points out “…the project and the project people were celebrated and at the same time overwhelmingly criticized and condemned to failure.”

The seeming paradox of concurrent celebration and condemnation underscores the incredible complexity of the project. It was an experiment, to be sure, for nothing of the magnitude or audacity had ever been attempted before, which left it wide open to all sorts of criticism and conjecture. Brigette Lively noted in her book, “From the start, the Colony had no lack of observers, critics, and experts from near and far. They all were rather uninhibited about voicing their often negative and mostly uninformed opinions.”

The source of their consternation was outlined by Orlando W. Miller in his heavily-footnoted book, The Frontier in Alaska and the Matanuska Colony (Yale University Press, 1975):

“The Matanuska Colony was hardly more than established before confusion arose about its origins and intended purpose. In Alaska the colony was regarded as an inept federal attempt to compensate for past neglect and to stimulate Alaskan development, and the relief and rehabilitation of rural families from depressed areas elsewhere was looked upon as a complication grafted on the plan, a perversion of what was, or should have been, the real aim–making Alaska grow.”

But part of the blame could be traced directly back to the controversial Rexford G. Tugwell. Described by Time magazine as “top man of the Brain Trust,” Tugwell believed intense planning was the key to avoiding economic and social upheaval. He was credited with statements such as: “Fundamental changes of attitude, new disciplines, revised legal structures, unaccustomed limitations on activity, are all necessary if we are to plan. This amounts, in fact, to the abandonment, finally, of laissez-faire.” and “Make no small plans, for they have not the power to move men’s souls.”

But part of the blame could be traced directly back to the controversial Rexford G. Tugwell. Described by Time magazine as “top man of the Brain Trust,” Tugwell believed intense planning was the key to avoiding economic and social upheaval. He was credited with statements such as: “Fundamental changes of attitude, new disciplines, revised legal structures, unaccustomed limitations on activity, are all necessary if we are to plan. This amounts, in fact, to the abandonment, finally, of laissez-faire.” and “Make no small plans, for they have not the power to move men’s souls.”

Tugwell’s plans were not small. The Gale Encyclopedia of Biography notes: “In some respects conservative, for he opposed welfare and believed in a balanced budget, Tugwell was intensely disliked by many opponents of the New Deal, in large measure because of his advocacy of planning, which in the 1930s was facilely associated with the type of planning carried on in the Soviet Union of Joseph Stalin.

“A suave, somewhat arrogant personality, Tugwell was readily caricatured and attracted considerable attention in the more conservative segment of the popular press as “Rex the Red, ” an appellation which was not only inaccurate but painful to Tugwell. Although he was not entirely satisfied with the New Deal, regarding it as too much of a patchwork, Tugwell was willing to remain in Washington as long as he considered himself useful to the administration.”

Rexford Tugwell eventually resigned due to congressional charges of socialistic and utopian leanings, but not before leaving an indelible mark on America’s domestic and economic policies. He made numerous contributions to American intellectual and public life over a 60-year period, and spent many years of worthwhile public service in Puerto Rico. His scholarly writings stimulated debate over many issues, including his longtime advocacies of planning and, later, of constitutional reform.

In the northern midwest states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, intensive commercial lumbering practices in the late-nineteenth century left parts of the region resembling a war zone of tree stumps and forest debris.

In the northern midwest states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, intensive commercial lumbering practices in the late-nineteenth century left parts of the region resembling a war zone of tree stumps and forest debris.

Concerned about the future prospects of the area, the local press, merchants, and bankers promoted the area for farm settlement around the turn of the century, and between 1900 and 1920, thousands of settlers moved into the region to carve out new farms from the cut-over forest land.

A United States Department of Agriculture Bulletin, No. 425, was published on October 24, 1916, titled Farming on the cut-over lands of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, authored by J. C. McDowell, Agriculturalist, and W. B. Walker, Assistant Agriculturalist. Available for five cents per copy, the introduction began:

“The cut-over district of northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota comprises an area of about 30,000,000 acres which is rapidly being developed into farms.”

After a summary of the bulletin, a description of the area followed:

“The high price of lumber in recent years has brought about the destruction of most of the pine forests in this region and has caused big inroads to be made into the forests of hardwood. Fires have also played an important part in the destruction of these northern forests. The harvesting of the crop of timber and its manufacture into lumber has made a few men very wealthy and for a long time has furnished employment to a large force of laborers at reasonably good wages.

“Strange as it may seem, the lumbermen rated the land that produced this heavy growth of timber as having little or no agricultural value. While this may be true of some of the swamp land and sandy belt areas, it is by no means generally true of this extensive cut-over district.”

“Strange as it may seem, the lumbermen rated the land that produced this heavy growth of timber as having little or no agricultural value. While this may be true of some of the swamp land and sandy belt areas, it is by no means generally true of this extensive cut-over district.”

With photos of idyllic farms and descriptions of “the little farm well tilled,” the booklet noted that “A large percentage of the settlers are foreign born. The are industrious and economical, and while their income is small, their expenses are low.” and then cautioned, “Buy good land. It is cheaper in the long run than poor land.”

As noted in the bulletin, the cutover settlers were often European immigrants who preferred working the land to work in America’s mines and factories. Comparatively cheap prices and favorable credit terms from lumber companies–who were eager to sell land they no longer needed and didn’t want to pay taxes on–allowed these families to own their farms, but as the booklet again explained, the cutover land was often rocky and covered with large tree stumps, and removing tree stumps and native rock to begin cultivation was expensive and frustrating labor.

The Great Depression wracked America in the early 1930s, leaving families destitute and men standing in breadlines. Hope was fading for thousands of Americans. Evangeline Atwood noted in her book that “…state and private welfare funds were running out. In some states forty percent of the population was on relief, and in some counties the percentage ran between eighty and ninety.

The Great Depression wracked America in the early 1930s, leaving families destitute and men standing in breadlines. Hope was fading for thousands of Americans. Evangeline Atwood noted in her book that “…state and private welfare funds were running out. In some states forty percent of the population was on relief, and in some counties the percentage ran between eighty and ninety.

“We caseworkers were at the point were a person had to be literally dying before we could provide hospitalization. A family had to be on the verge of disaster to be eligible for relief funds. We all knew such conditions could not continue without a revolution. The one bright star on the horizon was the change which was to take place in the White House. Maybe he could come up with the answer. Certainly Herbert Hoover and his advisors appeared helpless.”

The change on the horizon was, of course, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

~ ~ ~

In the late fall of 1933 and into the early months of 1934, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) began receiving inquiries about the feasibility of sending settlers to Alaska. A report, written by FERA architect David Williams, who had become intrigued by the idea of creating a colony in the Alaskan wilderness, was circulated among relief personnel in northwestern states. Great interest was exhibited, resulting in an exploratory trip to Alaska in June, 1934, by Jacob Baker, an assistant administrator of FERA. He was escorted to the Matanuska and Tanana Valleys by Colonel O. F. Olson, Manager of the Alaska Railroad, and A. A. Shonbeck, Chairman of the Alaska Democratic Central Committee.

In the late fall of 1933 and into the early months of 1934, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) began receiving inquiries about the feasibility of sending settlers to Alaska. A report, written by FERA architect David Williams, who had become intrigued by the idea of creating a colony in the Alaskan wilderness, was circulated among relief personnel in northwestern states. Great interest was exhibited, resulting in an exploratory trip to Alaska in June, 1934, by Jacob Baker, an assistant administrator of FERA. He was escorted to the Matanuska and Tanana Valleys by Colonel O. F. Olson, Manager of the Alaska Railroad, and A. A. Shonbeck, Chairman of the Alaska Democratic Central Committee.

Back in Washington Jacob Baker reported favorably to Lawrence Westbrook, director of FERA’s Division of Rural Rehabilitation, a part of Rexford Tugwell’s Resettlement Administration. Orlando Miller explains what happened next in The Frontier in Alaska and the Matanuska Colony:

“Westbrook was impressed, requested information from the interior and agriculture departments, prepared a memorandum on a possible experimental colony for Harry Hopkins, and was later called to see Roosevelt. The president asked three questions–whether the proposed colony could support a larger population, whether the proposed colony had any military importance, and whether relief families would find the Alaskan winters endurable. Westbrook stated his conviction, based on still incomplete information, that Alaska could eventually support a larger population at a higher standard of living than all of the Scandinavian countries combined. He thought that increased agricultural production in Alaska might play an important role in supplying the troops that could eventually be stationed there. As for the northern winters, he would select settlers from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, where the people were inured to hardships and where temperatures fell below those in the Matanuska Valley.”

On February 4, 1935, Executive Order Number 5967, signed by President Roosevelt, withdrew 8,000 acres of agriculturally promising land in the eastern part of the Matanuska Valley from homestead entry. On March 13 an additional 18,000 acres of grazing lands were withdrawn for the livestock of the Colony Project.

After that, preparations and official paperwork for the Colony Project slid into place rapidly, and Don Irwin explained what was also happening in early 1935 in his book, The Colorful Matanuska Valley:

“Meanwhile, in Washington, there were discussions between officials of the Department of the Interior and the FERA. It was agreed that the two organizations would undertake the Colonization Project jointly. Planning and execution of the project would be the responsibility of the FERA. The Department of Interior and the Alaska Territorial Government would cooperate fully. Funds appropriated under the Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933 would be used to finance the project. This act gave wide authority to the FERA administrator, Harry Hopkins, to grant funds to the several states and territories to help meet the costs of hardship relief, provide work relief, and alleviate the suffering caused by unemployment.

“Meanwhile, in Washington, there were discussions between officials of the Department of the Interior and the FERA. It was agreed that the two organizations would undertake the Colonization Project jointly. Planning and execution of the project would be the responsibility of the FERA. The Department of Interior and the Alaska Territorial Government would cooperate fully. Funds appropriated under the Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933 would be used to finance the project. This act gave wide authority to the FERA administrator, Harry Hopkins, to grant funds to the several states and territories to help meet the costs of hardship relief, provide work relief, and alleviate the suffering caused by unemployment.

“Early in February, 1935, solicitors acting for the FERA administrator drew up Articles of Incorporation for the Alaska Rural Rehabilitiation Corporation (ARRC). These instruments were sent, by airmail, to the Governor of Alaska in Juneau. The incorporating papers arrived at the Governor’s office during the rush of the 1935 Session of the Alaska Legislature. Action on filing the incorporating papers and returning them to the FERA office in Washington was delayed until the Legislative Session adjourned early in April.”

The delay created problems, but things were getting underway.